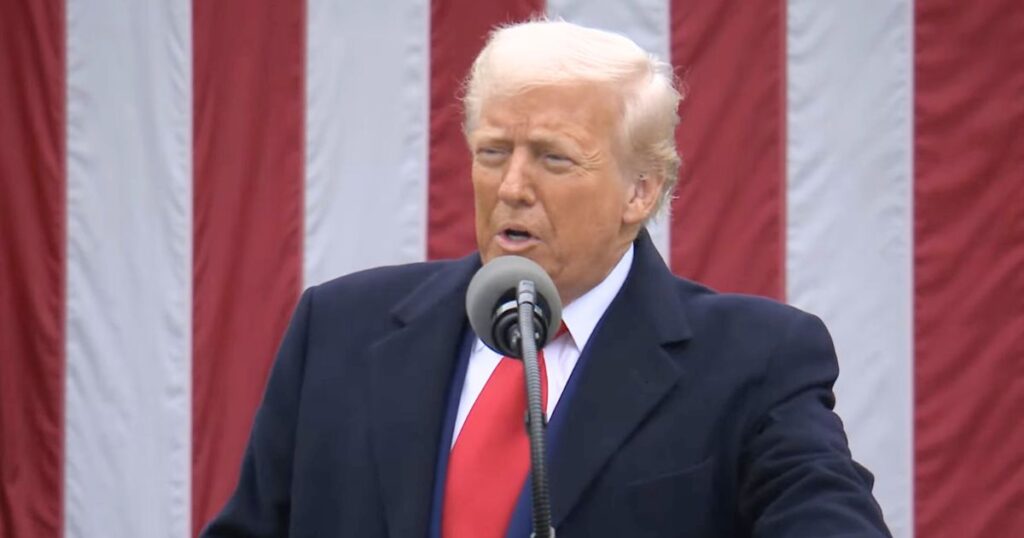

President Donald Trump’s promise of “Liberation Day” in April, which suggested that new tariffs would bring back manufacturing jobs, has not appeared in the job numbers so far. An analysis from The Washington Post revealed that factory payrolls have dropped since the president’s announcement.

U.S. factories employ about 12.7 million workers, down roughly 72,000 since Trump introduced the tariff plan in April, according to federal employment data cited by The Post. At the time, Trump claimed, “Jobs and factories will come roaring back into our country, and you see it happening already,” arguing that the import taxes would rebuild domestic industry.

Instead, manufacturing employment has decreased every month since April, as many producers faced higher costs for imported materials and uncertainty about how long the tariff system would stay in place. The losses have occurred in key industries like autos and high-tech manufacturing, which rely heavily on foreign components and specialized parts.

Michael Hicks, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University, told The Post, “2025 should have been a good year for manufacturing employment, and that didn’t happen. I think you really have to blame tariffs for that.” Hicks anticipates ongoing damage as demand adjusts. “The manufacturing job losses we see now are just the beginning of what will be a tough couple of quarters as manufacturing adapts to a new lower demand level,” he added.

The weak job situation also reveals a second issue for the administration’s trade policy. This is the legal dispute over whether Trump had the authority to impose global tariffs using emergency powers. The Supreme Court is considering a challenge to the tariffs implemented under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, and it may issue a ruling soon. Reuters reported that the justices seemed skeptical during the hearings regarding Trump’s power under the law.

If the court invalidates the tariff program, it could disrupt the revenue stream the administration has highlighted as proof that the policy is effective. Trump has claimed that tariffs have generated significant federal revenue, but businesses pay these taxes when goods enter the U.S., often passing those costs on through higher prices or reduced hiring.

Some manufacturers have cited declining demand and increasing global competition. In December, Westlake Corp., a Houston-based chemical producer, announced it would pause four production lines in Louisiana and Mississippi, leading to about 295 job cuts. The company pointed to excess global capacity and weak demand in commodity chemical markets as reasons for the shutdowns.

The Post reported that smaller and midsize manufacturers are facing intense pressure. They tend to have less capacity to absorb cost fluctuations and little leverage to quickly renegotiate supplier contracts. The paper also noted that broader economic factors, including high interest rates and a shift in consumer spending from goods to services, are complicating the situation. These trends can lower factory output and discourage hiring, even with rising investments.

The administration has claimed that job growth will follow as companies adjust their supply chains and increase domestic production. However, early employment data has undermined the central political message of “Liberation Day,” which suggested that tariffs would quickly lead to new factory jobs. With the Supreme Court decision still pending, manufacturers and investors are left wondering if the policy will last long enough to influence long-term business strategies.